Linda Connor

The Olson House

archival pigment prints

24 x 30 inches, edition of 5

Exhibition Portfolio: 24 x 30 inches, edition of 15

Library Portfolio: 12 x 14 inches, edition of 15

The Olson House Photographed by Linda Connor

Essay by Wanda M. Corn

The Olson House sits on a gentle hill near the seashore in Cushing, Maine, its clapboards deeply weathered and the inside rooms mostly empty. It is the kind of lived-in house one comes upon along the New England coast, a building steeped in the history of rural life, saltwater farming, and fishing. The original late eighteenth-century infrastructure has been expanded and altered by later generations. Its last inhabitants, Alvaro and his sister Christina Olson, worked and lived off the land and sea until they died within a month of one another in 1967-68. They are buried alongside their relatives in a tiny graveyard at the foot of the hill.

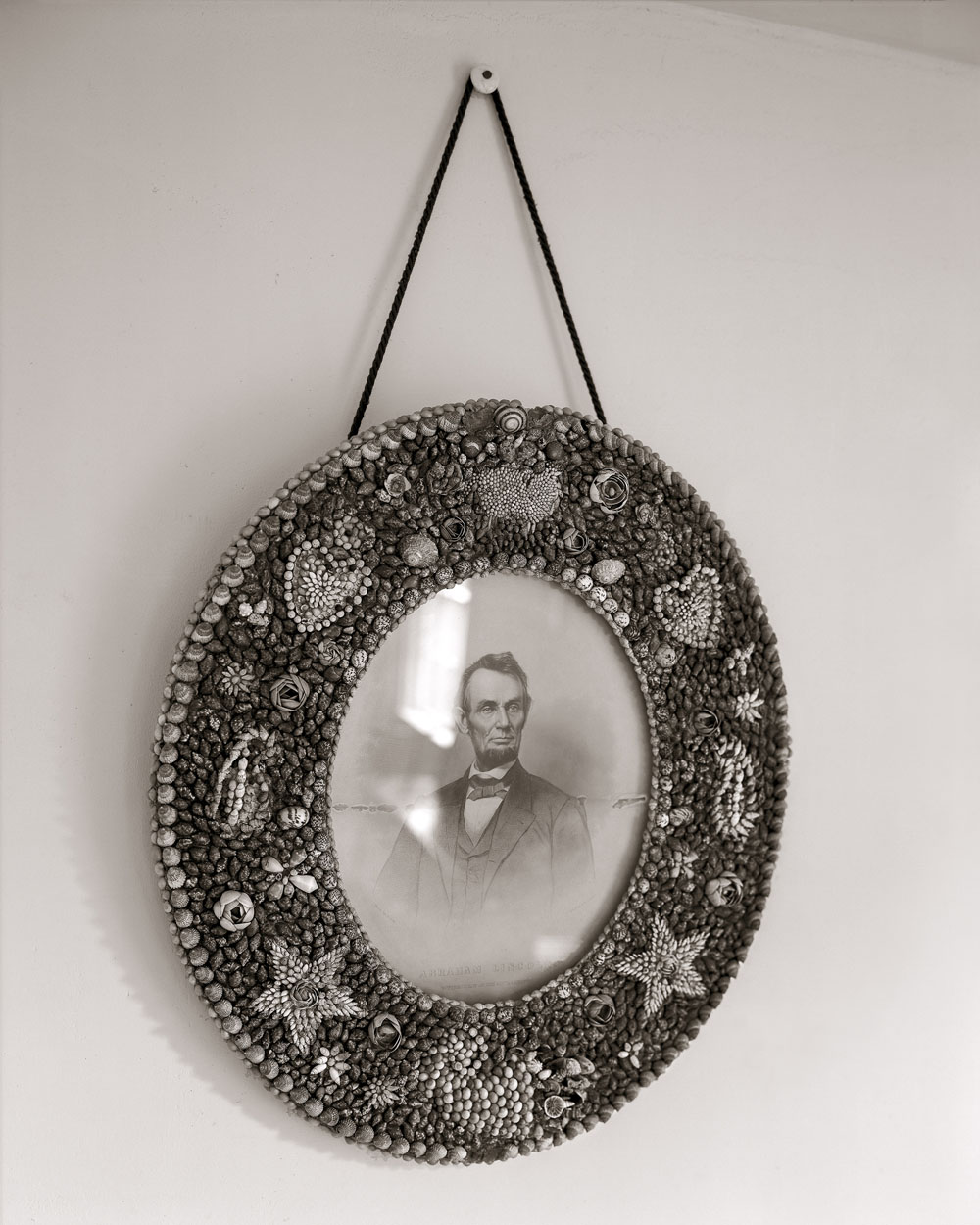

Nearby a new stone marks the grave of the artist Andrew Wyeth who died in 2009. Beginning in 1940, Wyeth painted the Olsons and their farm off and on for thirty years. Most famously, he included a spectral image of the house and its barn on the horizon in Christina’s World, a painting of 1948, acquired soon thereafter by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Christina had a degenerative disease that paralyzed her legs and lower torso; she used her arms to drag her inactive body around her circumscribed domain. By painting her from behind and against the hill, Wyeth created a lasting image of human longing.

Over time, Wyeth’s close association with the Olsons has given the site a mystique and modern patina. No longer an ordinary distressed New England house, it now commemorates one of the most famous paintings and painters in American history. Visitors make pilgrimages to the site to connect with both the artist and the house’s former inhabitants.

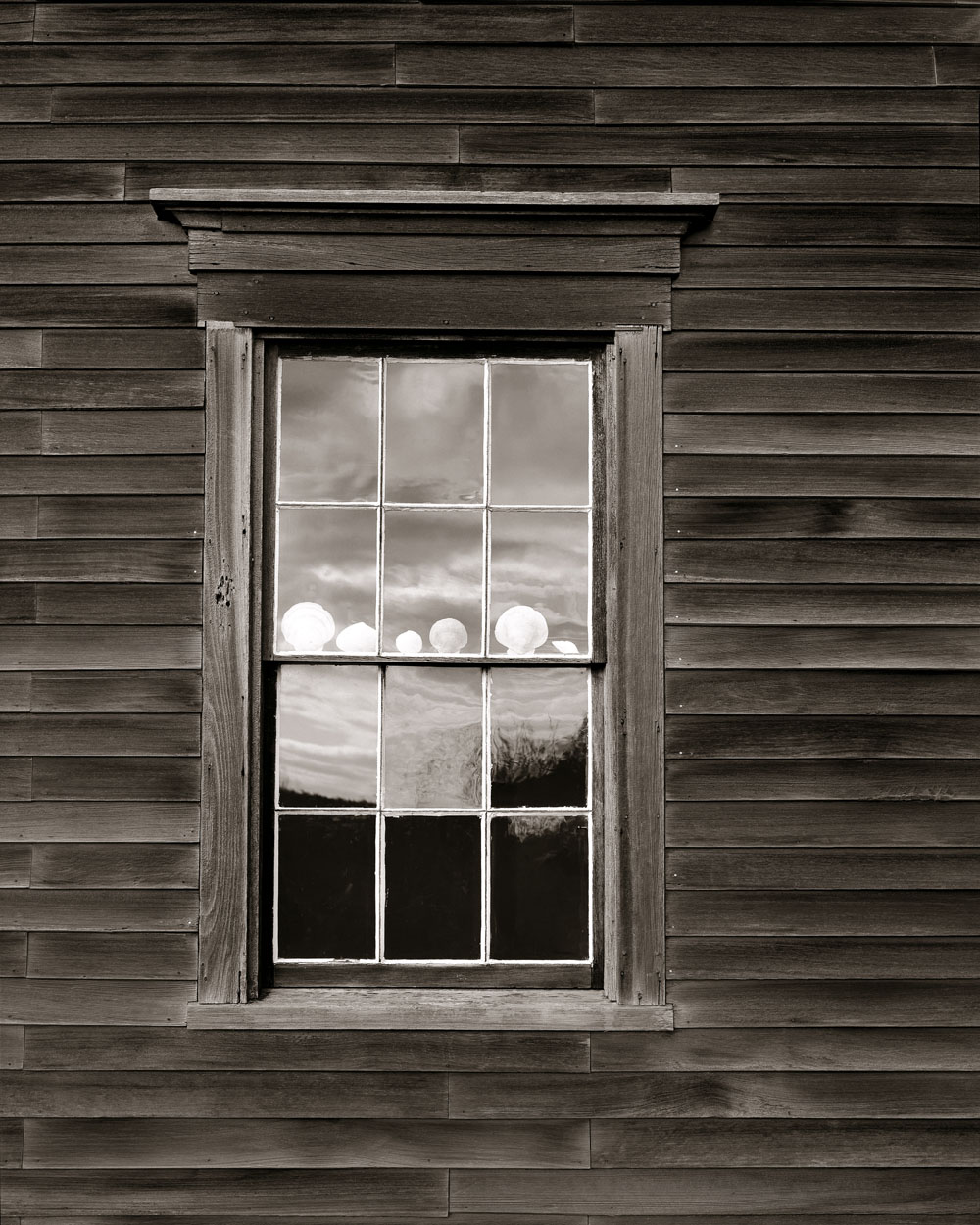

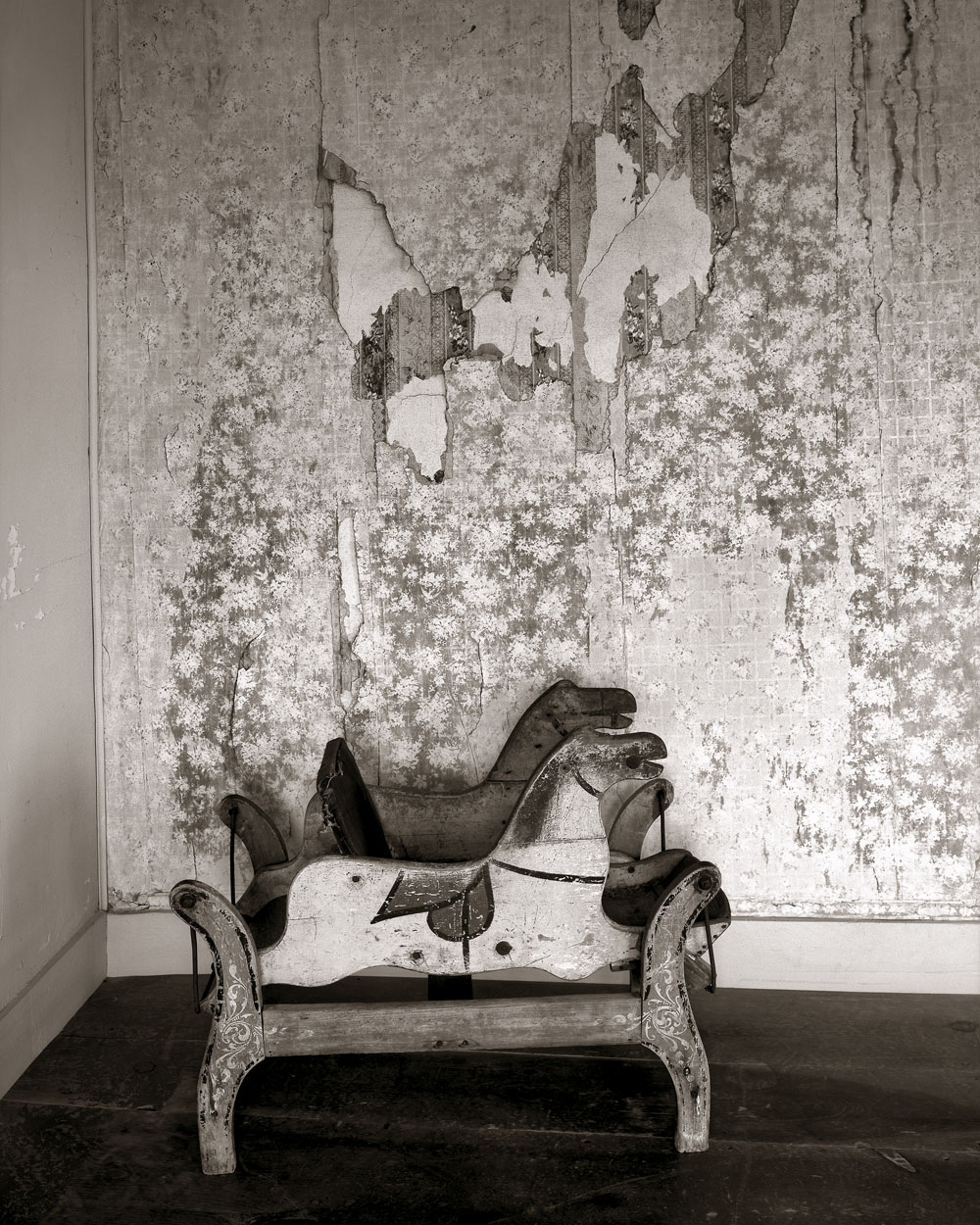

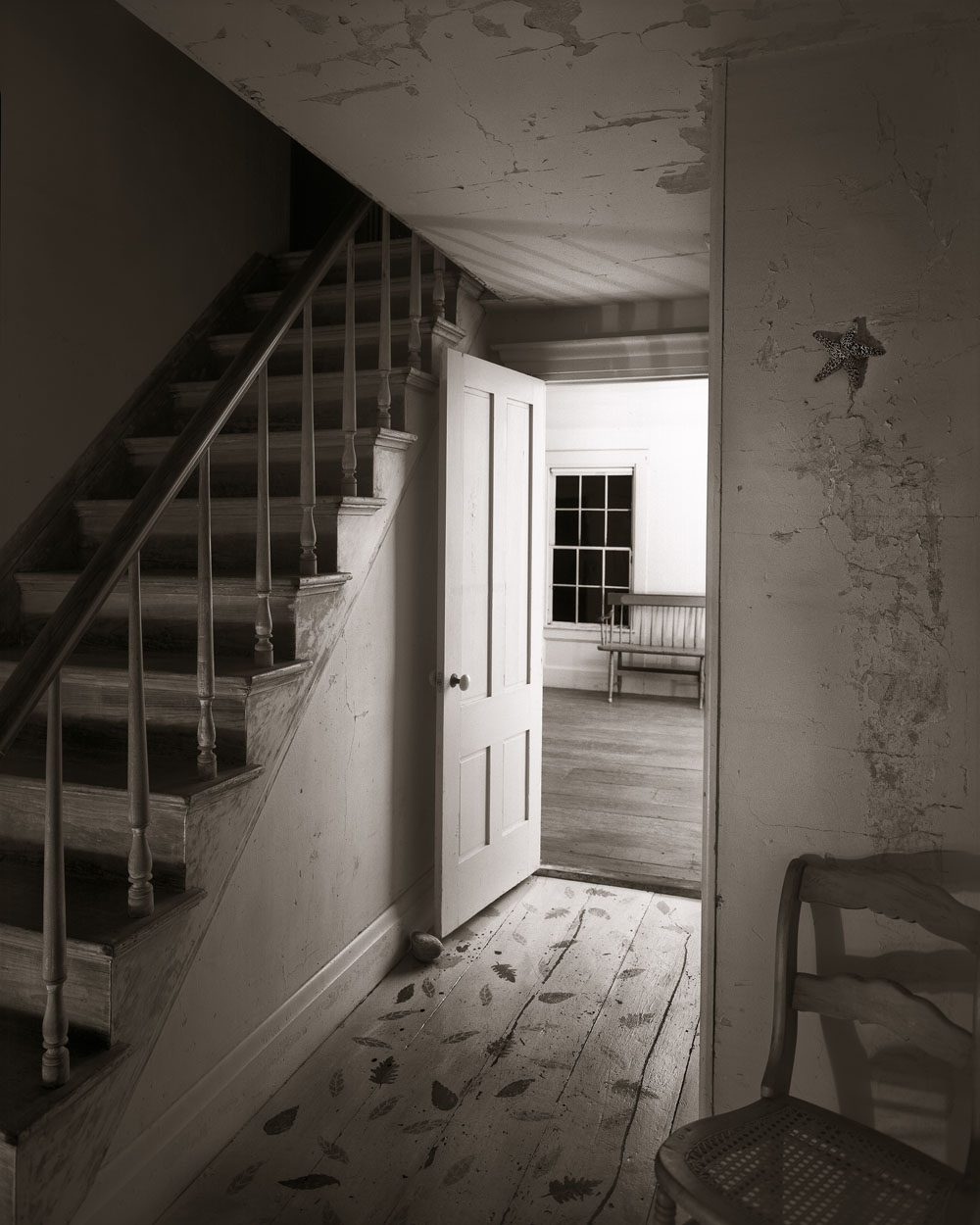

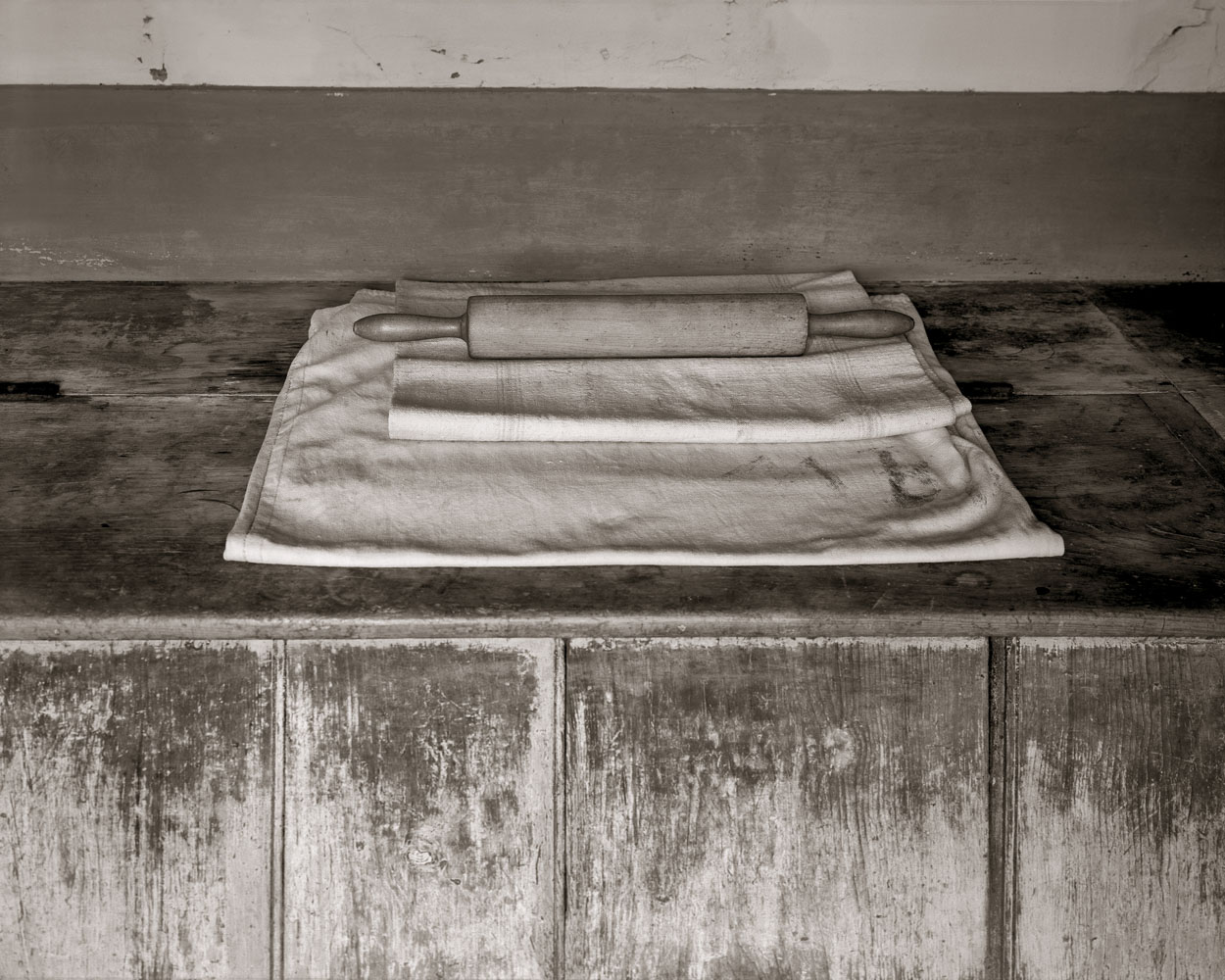

It is this aura that Linda Connor confronted when the Cincinnati Art Museum commissioned her to photograph the site in 2006 and used her contemporary images to provide a counterpoint to an exhibition of Wyeth’s earlier watercolors and drawings of the house and owners. A seasoned San Francisco photographer who had spent summers in Maine as a youth, Connor imprinted her own vision on the site. Wyeth’s Olson house was often melancholy and wistful, a site of human decay and hardship; Connor’s Olson house is mysteriously alive and animated. Using her favorite tool, an 8 x 10 view camera, Connor brings out the uneven and tactile textures of wood and glass burnished with age. In the few photographs where she referenced specific paintings by Wyeth, she created elegant, tonal renditions of sites he had painted: the hayloft, a wire basket on a hook, a roofline seen through an upstairs window, a doorway from the attached shed where Alvaro worked into the kitchen where Christina cooked. On other occasions, Connor self-consciously paid homage to well known photographs by Charles Sheeler, Frederick Sommers, and Walker Evans, and gave a nod to some of her own early work. But generally she followed her own instincts and made light as much a protagonist as the building. In a house of many windows, she found reflections animating walls, dark rooms leading into luminous ones, and light caressing tools and shells. In photographing the exterior of the house, she corralled available light to soften and dematerialize the structure so it seems more a vision than a thing.

On a nocturnal visit, the artist moved artificial lights from room to room, conjuring up uncanny beauty. The rooms become sacred space, radiating their own inner light. In one long outdoor exposure, the house takes on the character of an ancient monument standing against a black night sky streaked by the trails of stars changing their position around the North Star as the earth rotates. She was surprised and delighted when, upon developing her negative, she discovered she had captured a meteor and the quiet path of a satellite.

Linda Connor’s Olson House portfolio testifies to the way different artists relate to and interpret a similar landscape. Wyeth, with deep roots in Maine, knew the occupants well and his art was about them, their run-down house, and their struggles, hard work, courage, and humanity. Connor, a New Englander turned Californian, visited the property long after the house had been emptied, conserved, and opened to the public. She found primeval qualities in its raw unfinished timbers, peeling wallpaper, vacated rooms, and blank windows. Her Olson house is a Stonehenge in Maine, an old place with a murky history, animated today by spirits who dance in the light outside of time.